Vinyl record grooves work by encoding analogue audio signals in a physical form. When a stylus, commonly found on a turntable's needle, contacts the grooves, it vibrates according to the variations in the groove's shape. These vibrations are then translated into electrical signals, ultimately producing the sound that corresponds to the recorded music.

Groove Technology

The introduction of LPs and PVC records came alongside the development of microgrooves.

A microgroove refers to the tightly spaced and closely packed grooves on a vinyl record. These grooves are smaller and narrower compared to the wider grooves found on earlier shellac records. Microgrooves became the standard in the industry during the mid-20th century, allowing for longer playing times and improved sound quality.

The increased density of microgrooves enabled records to hold more audio information, contributing to the development of the LP (Long Play) format. This shift to microgrooves was a significant advancement in the vinyl record industry, enhancing the overall listening experience for music enthusiasts.

Introducing the RIAA Standard

In 1954, a standard of equalisation was introduced by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) which ensured that all music was mastered to the same specifications. In the context of vinyl records, equalisation is the process of adjusting the balance of frequencies during recording and reproducing to optimise the sound quality and overcome certain technical limitations.

In simple terms, the louder the bass frequencies are the wider the record grooves must be. The RIAA equalization curve boosts the bass frequencies during recording and attenuates them during playback, while doing the opposite for high frequencies. This standardised approach ensures consistent and reliable playback across different systems and equipment. Most modern turntables and vinyl records adhere to the RIAA standard to maintain compatibility and ensure accurate reproduction of recorded audio.

This way, the grooves can be kept at a certain (micro) width and smaller grooves equal longer runtimes. Thanks to the RIAA time per side could be increased to 22 minutes.

The anatomy of a record groove is best thought of in terms of sound waves. The groove is essentially a 3D representation of the waves – and so the stylus needle brushes along them and reproduces the track. Check out the video above where a scientist has used an electron microscope to get up close and slow-motion views of record grooves.

As record technology improved, more complex sound was able to be recorded and represented on records.

Stereophonic recording came about in 1931, and we still use it today to provide a greater balance and sense of space to a recording. It essentially records on two planes rather than one (monophonic needles only move horizontally).

In a mono record groove, the variations in depth and shape represent the combined audio signals for both channels. The needle moves up and down in a single channel, capturing the overall sound. In contrast, stereo records have two separate channels within the groove, and the stylus is designed to pick up the lateral movements representing the left and right channels independently. This allows for a spatial separation of sounds, creating a more immersive listening experience when played back through stereo speakers or headphones.

Occasionally you might notice you hear an echo before or after a loud sound – particularly at the start of a record. This is when some of the cutting stylus accidentally transferred some of the information from another groove through the ‘groove wall’ – this is one of few drawbacks of having such thin grooves.

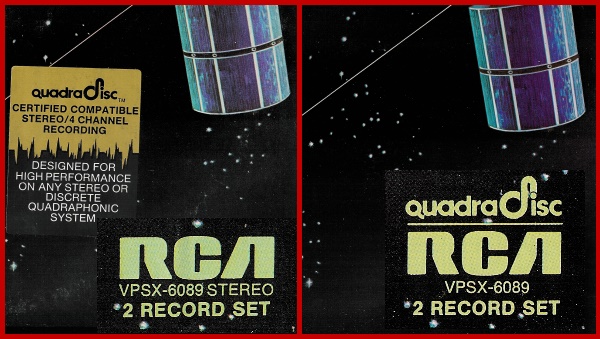

quadraphonicquad.com

In the 70s there were attempts to introduce Quadraphonic records, but they didn’t hit it off. As you may have guessed, this method used four channels for recording. They weren’t successful due to technical issues with the discs, they were more expensive, and anyone who had a collection would need four speakers instead of two! They look just like a normal record unless you get up really close to the grooves.

It was still an important development, however, and has been essential for surround sound in places such as cinemas.

1 comment

I can’t say I’ve ever heard an “echo” due to transfer through a groove wall, these effects are normally due to “print through” on magnetic master tapes and is responsible for a long lasting argument among mastering professionals as to how a master tape should be stored, “tail in” or “tail out” as the most obvious effect is being able to hear a track faintly before it starts. I have many 7” singles that very clearly have a “pre echo” mostly from the 70s!